Breadth-First Search (BFS)

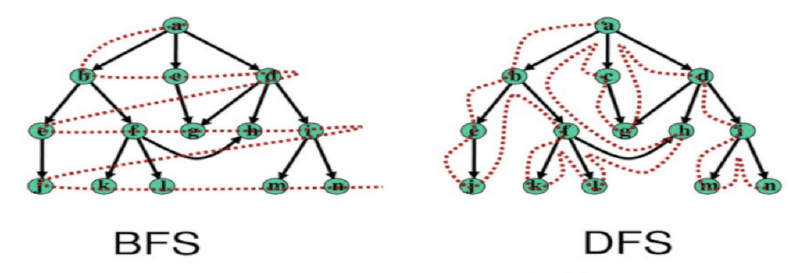

Breadth-First Search (BFS) is a fundamental graph traversal and search algorithm. It systematically explores a graph level by level, starting from a designated start node. BFS will explore all paths one step away from the starting point, then all paths two steps away, and so on, ensuring that the shortest path is found first.

How BFS Works

Initialization:

- Start with a queue data structure, typically implemented using

collections.dequein Python for efficient FIFO (First-In, First-Out) operations. The queue initially contains only the start node. - Maintain a

visitedset (or list) to keep track of nodes that have already been explored to avoid cycles. - Optionally, a

parentdictionary is used to store the predecessor of each visited node, allowing for path reconstruction later.

- Start with a queue data structure, typically implemented using

Iteration:

- While the queue is not empty:

- Dequeue a node from the front of the queue. This is the node currently being explored.

- For each neighbor of the current node:

- If the neighbor has not been visited:

- Mark the neighbor as visited.

- Enqueue the neighbor.

- Record the current node as the parent of the neighbor (if path reconstruction is needed).

- If the neighbor has not been visited:

- While the queue is not empty:

Termination:

- The algorithm terminates when the queue is empty, indicating that all reachable nodes from the start node have been explored.

- If a target node is specified, the search can terminate as soon as the target node is dequeued. The

parentdictionary can then be used to reconstruct the shortest path from the start node to the target.

Pros of BFS

- Completeness: BFS is complete, meaning that if a path exists between the start node and the target node, BFS will find it.

- Optimality: BFS guarantees finding the shortest path (in terms of the number of edges) between the start node and the target node in an unweighted graph.

- Simplicity: The algorithm is relatively straightforward to understand and implement.

Cons of BFS

- Memory Consumption: BFS can consume a significant amount of memory, especially for large graphs. This is because it stores all the nodes at the current level in the queue. In the worst-case scenario, where the entire graph needs to be traversed, the queue can grow to hold a large fraction of the total number of nodes.

- Not Suitable for Weighted Graphs: BFS is designed for unweighted graphs. It finds the shortest path based on the number of edges, not the total weight of the edges. For weighted graphs, algorithms like Dijkstra’s algorithm are more appropriate.

Where BFS Excels

- Finding Shortest Paths (Unweighted Graphs): Its primary strength is finding the shortest path in graphs where all edges have the same weight (or no weight).

- Connectivity Testing: Determining if two nodes are connected in a graph.

- Web Crawlers: BFS can be used to crawl web pages, exploring links level by level.

- Social Network Analysis: Finding the shortest chain of connections between two people in a social network.

- GPS Navigation: In scenarios where minimizing the number of “hops” is more important than the total distance (e.g., minimizing the number of transfers in public transportation).

Where BFS Fails

- Weighted Graphs: As mentioned earlier, BFS is not suitable for finding the shortest path in graphs where edges have different weights.

- Very Large Graphs: The memory requirements of BFS can become prohibitive for very large graphs.

- Graphs with High Branching Factors: Graphs where each node has many neighbors can lead to a large queue and high memory consumption.

Common Use Cases

- Pathfinding in Games: Finding the shortest path for a character to move in a game environment (where all moves have the same cost).

- Network Routing: Discovering network topology and finding the shortest paths between devices.

- Garbage Collection: Tracing reachable objects in memory to identify those that can be safely deallocated.

- Peer-to-Peer Networks: Finding the closest peers in a peer-to-peer network.

Depth-First Search (DFS)

Depth-First Search (DFS) is another fundamental graph traversal and search algorithm. Instead of exploring a graph level by level like BFS, DFS explores as deeply as possible along each branch before backtracking. DFS will pick a path and follow it to the end, then backtrack to the last branching point and try a different path.

How DFS Works

Initialization:

- Start with a stack data structure, typically implemented using a Python list. The stack initially contains only the start node.

- Maintain a

visitedset (or list) to keep track of nodes that have already been explored to avoid cycles. - Optionally, a

parentdictionary is used to store the predecessor of each visited node, allowing for path reconstruction later.

Iteration:

- While the stack is not empty:

- Pop a node from the top of the stack. This is the node currently being explored.

- If the node has not been visited:

- Mark the node as visited.

- For each neighbor of the current node:

- If the neighbor has not been visited:

- Push the neighbor onto the top of the stack.

- Record the current node as the parent of the neighbor (if path reconstruction is needed).

- If the neighbor has not been visited:

- While the stack is not empty:

Termination:

- The algorithm terminates when the stack is empty, indicating that all reachable nodes from the start node have been explored.

- If a target node is specified, the search can terminate as soon as the target node is popped from the stack and found to be the target. The

parentdictionary can then be used to reconstruct a path (not necessarily the shortest) from the start node to the target.

Pros of DFS

- Memory Efficiency: DFS generally requires less memory than BFS, especially for deep graphs. It only needs to store the nodes on the current path being explored, rather than all the nodes at the current level (as BFS does).

- Simple Implementation: DFS can be implemented recursively, making the code very concise (though the iterative version, using a stack, is also straightforward).

- Good for Finding Any Path: If you just need to find a path between two nodes (not necessarily the shortest), DFS can be faster than BFS.

Cons of DFS

- Not Guaranteed to Find Shortest Path: DFS does not guarantee finding the shortest path. It finds a path, but that path might be much longer than the shortest path.

- Can Get Stuck in Infinite Loops: If the graph contains cycles and the

visitedset is not used correctly, DFS can get stuck in an infinite loop, exploring the same nodes over and over. - May Explore Irrelevant Paths: DFS can explore paths that are far away from the target node before finding the target.

Where DFS Excels

- Detecting Cycles: DFS is well-suited for detecting cycles in a graph. If, during the traversal, you encounter a node that has already been visited (and is still on the stack), it indicates the presence of a cycle.

- Topological Sorting: DFS is used in algorithms for topological sorting of directed acyclic graphs (DAGs).

- Path Existence Checking: Determining if a path exists between two nodes, even if the shortest path is not required.

- Solving Puzzles: DFS can be used to explore possible solutions in puzzles and games (e.g., solving a maze, finding a solution to a Sudoku puzzle).

Where DFS Fails

- Finding Shortest Paths: When the shortest path is required, BFS or other algorithms like Dijkstra’s algorithm are better choices.

- Graphs with Long Paths: In graphs with very long paths, DFS might take a long time to find the target node or explore the entire graph.

- Infinite Graphs: DFS can get lost in infinite graphs if there is no clear termination condition.

Common Use Cases

- Cycle Detection: As mentioned earlier, DFS is commonly used to detect cycles in graphs.

- Topological Sort: Ordering tasks in a project based on dependencies.

- Maze Solving: Finding a path from the entrance to the exit.

- Backtracking Algorithms: Solving problems where you need to explore different possibilities and backtrack when a dead end is reached (e.g., solving constraint satisfaction problems).

- Game AI: Implementing AI for games where the AI needs to explore possible moves and evaluate their consequences.

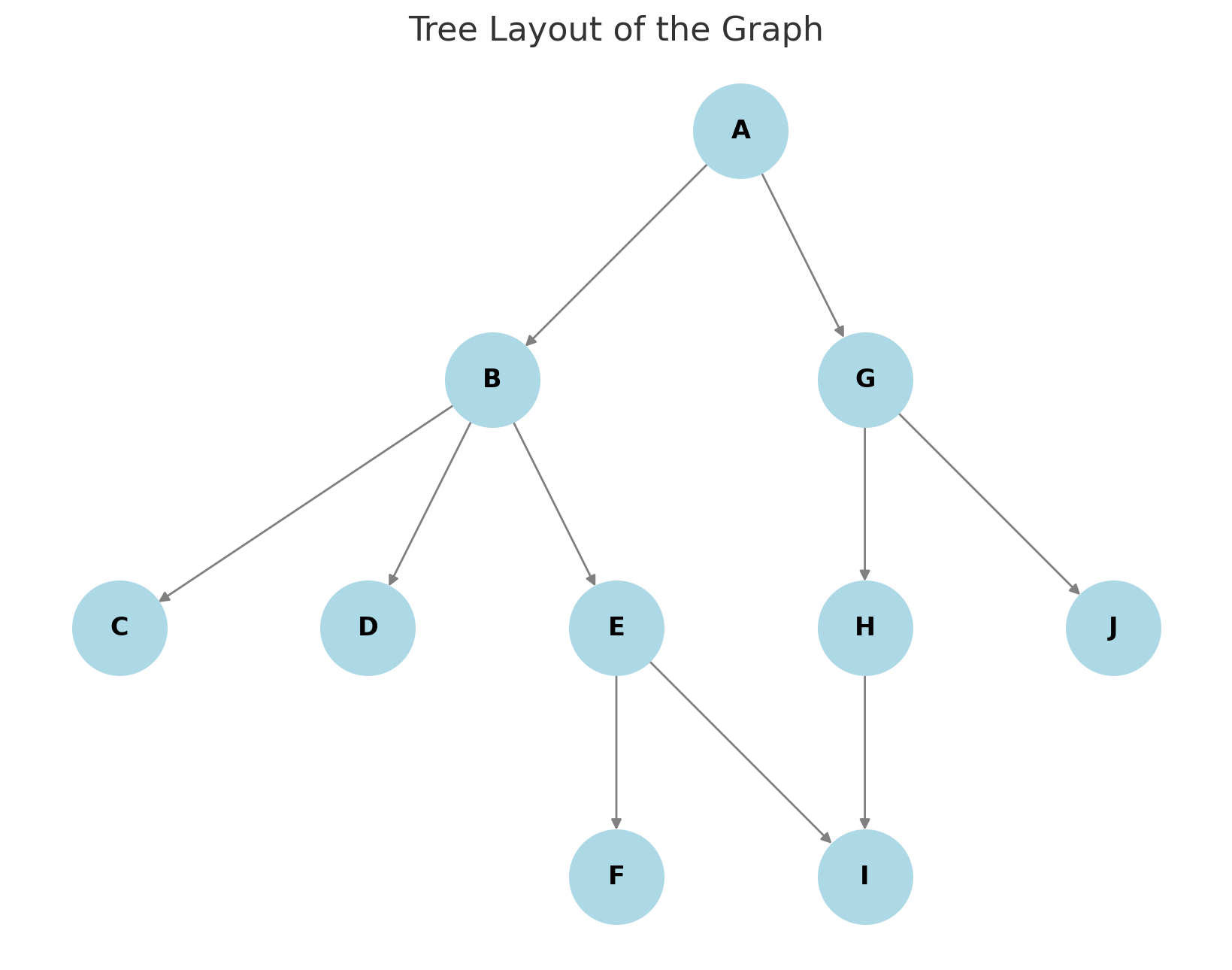

I added below two examples, one for BFS and another for DFS. The graph used was the one on the image below:

This is the output of both, where we can notice the difference:

bfs.py:

| |

Visitation Order:

- Level 0: [‘A’]

- Level 1: [‘B’, ‘G’]

- Level 2: [‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’, ‘H’, ‘J’]

- Level 3: [‘F’, ‘I’]

It visits all nodes on the current level before going to the next level.

dfs.py:

| |

Visitation Order:

- ‘A’: Start node, popped first.

- ‘G’: From ‘A’, neighbors are [‘B’, ‘G’]. Added to stack as [‘B’, ‘G’], so ‘G’ is popped next (LIFO).

- ‘J’: From ‘G’, neighbors are [‘H’, ‘J’]. Added as [‘B’, ‘H’, ‘J’], ‘J’ popped.

- ‘H’: From ‘J’, no new neighbors. Stack now [‘B’, ‘H’], ‘H’ popped.

- ‘I’: From ‘H’, neighbor ‘I’ added, popped next.

- ‘B’: Stack now [‘B’], popped after ‘G’’s subtree is exhausted.

- ‘E’: From ‘B’, neighbors [‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’]. Added as [‘C’, ‘D’, ‘E’], ‘E’ popped.

- ‘F’: From ‘E’, neighbors [‘F’, ‘I’]. ‘I’ already visited, so ‘F’ added and popped. Target found, stops.

It goes deep into ‘G’’s branch (‘G’ → ‘J’ → ‘H’ → ‘I’) before backtracking to ‘B’ and then ‘E’ → ‘F’.

BFS Example (Click to Show/Hide)

| |

DFS Example (Click to Show/Hide)

| |